|

|

|

|

Studia

Historica Septentrionalia 43 |

|

|

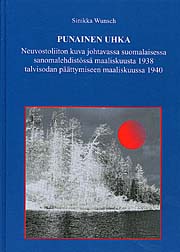

Sinikka Wunsch,

Punainen uhka.

Neuvostoliiton kuva

johtavassa suomalaisessa sanomalehdistössä maaliskuusta 1938

talvisodan päättymiseen maaliskuussa 1940.

Pohjois-Suomen Historiallinen Yhdistys, Rovaniemi 2004. 381 pages.

|

|

With english summary:

The Red Threat: The Image of the Soviet Union in Leading Finnish

Newspapers from March 1938 until the End of the Winter War in March

1940.

This dissertation investigates how the leading Finnish newspapers

represented the Soviet Union between March 1938 and March 1940. The

newspapers include, first, the two Finnish papers with the widest

circulation and, second, the papers of the main political parties. The

former are the politically independent Helsingin Sanomat and

Hufvudstadsbladet and the latter former are Ajan Suunta, the organ of

the right-wing Patriotic People’s Front (Isänmaallinen kansanliike),

Uusi Suomi, the representative of the National Coalition Party

(Kansallinen Kokoomus), Ilkka, the organ of the Agrarian Union

(Maalaisliitto), Turun Sanomat, the representative of the National

Progressive Party (Kansallinen Edistyspuolue) and Suomen

Sosialidemokraatti, the organ of the Social Democratic Party

(Sosialidemokraattinen puolue). In order to see whether there are any

specifically Finnish features in the image that these papers created

and sustained of the Soviet Union they are compared with two foreign

papers. Both Dagens Nyheter (Sweden) and the New York Times (the

United States) were quality papers with fine international reputation.

Both were published in countries which were neutral at the time and

therefore not subject to war-time censorship.

The central concepts in the study are

“image” and “opinion”. In historical image research, “image” refers to

a comprehensive conception which is based on a person’s own set of

values and comprises the subject as a whole. A human being uses images

to structure his or her world and reality, while an opinion pertains

to an individual event to which the person can take a stand regardless

of his or her values and world views.

The study falls into two main parts: The

first comprises the pre-war period from the beginning of March 1938 to

October 6, 1939. The second period starts in October 7, 1939, and ends

right after the termination of the Winter War in March 1940. The

circumstances under which Finnish journalists worked changed

drastically after the Soviet Union called the representatives of the

Finnish Government to Moscow for negotiations at the beginning of

October 1939. A similar invitation had recently been issued to the

three Baltic countries Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. They had quickly

agreed to enter into alliance with and to ceded military bases to the

Soviet Union. In Finland, the Soviet demands met with severe

opposition. There was no intention of entering the alliance. Although

there was no censorship as yet, the state and official propaganda

organizations already exerted influence on the newspapers.

The first chapter of the study deals with

the historical image of Russia and the Soviet Union in the West and in

Finland. The focus then shifts to the image of the Soviet Union as it

was manifested in Finnish newspapers in 1938 and 1939. In analyzing

the way that the Finnish papers represented the domestic affairs of

the Soviet Union I focus have focused on the following variables:

Soviet society and the communist system, the standard of living in the

Soviet Union, the Red Army, the leadership and the people. The next

chapter s is discusses the image that the Finnish papers created of

Soviet foreign politics and its changes during 1938 and 1939. The

chapter proceeds chronologically, because the papers’ image reacted to

changes in the international position of the Soviet Union, which was

weak and isolated in 1938 but grew constantly stronger after that. A

major change took place in the way that the Soviet Union was

represented during the Moscow negotiations in October and November

1939. During less than two months, the Finnish image of the Soviet

Union increasingly became the image of an enemy.

In the section dealing with the time of the Winter War I pay have paid

attention to the same variables that I usedd in examining the pre-war

image of the Soviet Union. However, the Finnish papers were no longer

interested in Soviet foreign politics in the more general sense after

the Soviet attack on Finland and the outbreak of the war. The other

features – Soviet society, the standard of living in the Soviet Union,

its leaders and its people – were still discussed. The views of the

Finnish newspapers of the Red Army were those of a country engaged in

defensive warfare of defense. They naturally made use of the

experiences that had been acquired on the front and on the home front

(in the civilian areas that were bombed by the Soviets).

During the whole period under study, the

Finnish newspapers’ image of the Soviet Union was colored both by

their own ideological commitments and by the narrative traditions that

had been formed during the long, conflict-ridden history of Finland

and Russia. The pieces published in Ajan Suunta, Uusi Suomi and Ilkka

were marked by the papers’ right-wing ideology already before the war,

particularly when they described the internal conditions in the Soviet

Union, while socialist ideology influenced the way that Suomen

Sosialidemokraatti described the Soviet Union was described in Suomen

Sosialidemokraatti. The image that different newspapers had of the

Soviet Union thus had somewhat different roots. This is also true for

their war-time writing, although the fact that the Soviet Union was

now the common enemy brought the papers closer to each other. The

image of the Soviet Union became more uniformly negative when many of

the black-and-white stereotypes formerly cultivated only in the

right-wing papers were adopted by the politically neutral and

left-wing newspapers as well.

By and large, it can be said that the

Finnish newspapers’ image of Russia and the Soviet Union became more

openly ideological, the tenser the situation became in Europe and the

more the newspapers resented Soviet foreign politics. The papers’

opinion of the internal affairs of the Soviet Union also influenced

the overall image. For instance, the Finnish newspapers took a very

negative view on the Moscow show trials in 1938 and resented the fact

that the Soviet Union chose to regard Finland as one of the Baltic

states in 1939, and the way they represented the Soviet Union became

more negative as a result.

During the pre-war period, bourgeois

papers used the Soviet Union and its social chaos to illustrate what

would await socialist society in Finland, too. Papers on the left

could also see some positive, genuinely socialist features in the

development of Soviet society. When Finnish journalists were

describing e.g. Soviet terror, the position of the Soviet citizen, or

the standard of living or forms of land ownership in the Soviet Union,

they were, in an inverse image as it were, also praising the democracy

and welfare at home. Occasionally, for instance when Ajan Suunta, Uusi

Suomi and Ilkka represented the Soviet collectivized agriculture in an

extremely dismal light, Suomen Sosialidemokraatti criticized them for

vilifying the Soviet Union. The views of the politically neutral

papers Helsingin Sanomat and Hufvudstadsbladet, as well as the liberal

Turun Sanomat, did not essentially differ from those of the

above-mentioned right-wing papers, although they avoided the most

poignant linguistic expressions when they wrote about the Soviet

Union.

Since 1934, the Soviet Union had hinted

at the possibility of attacking Finland if a third party, Germany for

instance, used would use Finnish territory to threaten the Soviet

Union. Against this background, it is easy to see why Finnish

newspapers were interested in Soviet domesticinternal and foreign

affairs during the whole period under study. For instance, the great

purge of the Red Army was seen in Finland as a sign of the

disintegration and weakness of the Soviet armed forces, and a military

insurrection was regarded as possible, or even probable, in 1938.

Events like this gave birth rise to wishful images of generals raising

against Stalin. Since such images are absent from the New York Times

and Dagens Nyheter, they must be firmly rooted in Finnish hopes and

wishes.

In 1938, the international position of

the Soviet Union was weak. It was not regarded as a major military

power or otherwise a significant player in European politics, partly

because it was handicapped by its domestic problems. The great

willingness of the Finnish bourgeois papers to dwell on these problems

betrays their negative image of the Soviet Union. Problems were taken

as signs of the hoped-for result: the breakdown of the Soviet Union.

In the New York Times and Dagens Nyheter the political isolation of

the Soviet Union is indicated above all by the scarcity of writing on

it. When these papers analyzed the political development of Europe,

particularly after the Munich crisis in the latter part of the 1938,

they often overlooked the Soviet Union altogether. They became

interested in the Soviet Union only after Germany had German occupied

ation all of Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939 and Britain, France

and the Soviet Union had entered into negotiations to prevent further

German expansion in Europe.

Although foreign newspapers, too, wrote about the problems and

weaknesses of Soviet society and army, particularly before the spring

of 1939, they were not as exclusively concerned with them as the

Finnish papers. For instance, they noted that the Soviet army was

constantly increasing its supply of men and arms. The Finns started to

did not start to pay attention to such things only in until 1939, when

war was already imminent in Europe. Even then, their interest was

motivated above all by domestic affairs: the bourgeois papers used the

image of the increasingly powerful Red Army that was gaining strength

as an argument for quickly enlarging the military budget. This

argument was absent from the workers’ paper, because the Social

Democratic Party was strongly against increasing military expenditure.

The way that the Finnish newspapers

represented the ’ representations of the Soviet Union not only

reflected their own conceptions and ideologies, but these

representations could also be politically useful. y could also be used

in political debates. The clearest example of such political uses can

be found in the way that Eljas Erkko, the owner and editor-in-chief of

Helsingin Sanomat, used his paper in the debate on Finnish foreign

politics in 1938 and 1939. In this debate, the paper used the current

image of the Soviet Union to emphasize the dangers constituted first

by the League of Nations and later by the various guarantees that were

demanded by the Soviet Union. Erkko, who was a member of the liberal

Progressive Party, also employed used the image of the Soviet Union in

his personal campaign for the post of Foreign Minister. After Erkko

had won the post, the representatives of the Soviet Union could often

read about the views of the Finnish Government from the pages of

Helsingin Sanomat. The paper was not just a source of information but

also a political tool and an agent of power.

Parts of the Finnish press were thus active in their relationship to

the Soviet Union during the pre-war period. Helsingin Sanomat assumed

the key role already in the spring of 1938, when Finland dissociated

itself from certain regulations enacted by the League of Nations.

During Erkko’s time as Foreign Minister its role was further

accentuated as “the voice of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” Other

papers followed its lead so closely that the ideological differences

between the papers became mere differences of tone. With the growing

tension between Finland and the Soviet Union grew, some of the papers

started to write to two different target groups. On the one hand, they

papers aaddressed their own readers. On the other hand, Helsingin

Sanomat also wrote to foreign, especially to Soviet audiences, and

Suomen Sosialidemokraatti, too, also occasionally furnished the Soviet

Union with information about the morale of the Finnish working people.

Already during the summer of 1939, a more

threatening image of the Soviet Union had emerged in the Finnish

printed media. The image reflects the concern that was caused by the

fact that the Soviet Foreign Minister Vjatseslav Molotov treated

Finland as one of the Baltic countries. Molotov ignored Finnish claims

to neutrality. The Finns became even more worried when after the

German-Soviet nonaggression pact was signed in August, and Germany and

the Soviet Union divided Poland between them. The fate of the Baltic

countries at the end of September and the beginning of October further

emphasized the Soviet menace and accentuated the threatening and

negative features in the Finns’ image of the Soviet Union. Helsingin

Sanomat, the spokesman of the Government, or at least of the Foreign

Minister, was already speaking about “Russian imperialism.”

In October and November the way that the newspapers wrote about the

Soviet Union became more closely regulated, due to thanks to discreet

official interventionvolvement. Finnish propaganda organizations had

been on the making since 1937, and they started to operate with full

force in the autumn of 1939, when the Moscow negociations were under

way and the Finnish Army was being mobilized.

As soon as the crisis broke out, Army

information officers and organs started to supply the papers with

instructions on what and how to write, as well as with ready-made

pieces to publish. Before mid-October, the representatives of the

press were already regularly informed what it was desirable for them

to write and not write about. Even before the war, the papers followed

these instructions closely. In fact Tthey had little choice, because

emergency laws and acts allowed the Government to suppress any piece

of writing it found harmful. Regular war censorship was introduced

only in December 5, when the war that would later become known as the

Winter War had already been waged for several days (the Soviet Union

had attacked Finland on November 30th).

There is no sign that the press was

reluctant to follow the instructions. It considered itself as part of

the warring nation from the start. It attacked the enemy with words

and dutifully followed the instructions it had received. It can thus

be said that Finland not only fought successfully on the front but was

also mentally well prepared for the propaganda war.

For someone interest in the study of

image of the enemy, the Winter War is an ideal case. It was triggered

off by a unilateral attack, it was intensive and, lasting only 105

days, it was too short for a opposition to emerge or for war fatigue

to set in. The way that the enemy was represented during the war was

stereotyped, but expressive and suggestive, and that image was

willingly adopted by the people that was engaged in a defensive war.

The Soviet Union, whose dogmatically ideological propaganda made few

concessions to reality, made it easier for Finnish papers to construct

and to sustain hold on to their stereotyped image of the enemy. The

information provided by the Soviets did not adapt to the changing

circumstances but followed a ready-made formula. The Red Amy had been

instructed to take Finland in two weeks. Although their attack was not

successful, the Soviet propaganda stubbornly insisted that the Red

Army was triumphantly liberating Finnish workers and peasants. When

the attack was repelled by Finnish forces, Soviet propaganda seemed

ridiculous and thereby ended up serving Finnish rather than its own

purposes.

Together with the major ground attack, the Soviet Union also launched

an a aerial attack against civilian targets. In late 1939 and early

1940, large-scale airstrikes on civilians were still so new in

European warfare that Finnish propaganda was able to present them as

terrorist acts directed at civilians. Civilized nations, the Finns

said, could never commit such acts. This claim became part of the

Finnish image of the enemy, and it found support in the

conflict-ridden history of the two countries. In Finnish propaganda,

Russia / Soviet Union was established as the arch-enemy, who had

during centuries taken every opportunity to attack Finland for

centuries. The bourgeois press in particular liked to remind its

readers of the period known as the Great Hate (1713-1721), when

Russian soldiers had occupied Finland and subjected the civilian

population to violent and arbitrary treatment.

The Finnish image of the enemy became

more unrealistic in the course of the war. Neither the press nor the

readers wanted to face the facts about the SSoviet resources. The

Soviet Union had been prepared to fight a war which lasts a couple of

weeks at the most. However, Finland surprised the world with its

military prowess and caused much damage to the great power. The Finns

consequently held regard the Red Army in very low regard. A few weeks

into the war, the press started to conjecture that it will be the

Soviet Union, not Finland, that will loose the war. When the battle of

Suomussalmi ended in Soviet defeat in January, belief in the Finnish

military superiority became unshakeable.

The way that Soviet society, its leaders

and its people were represented after the outbreak of the war was

based on the negative image that had been created before the war, most

importantly in 1938, the year of terror in the Soviet Union. During

the three war months, it was elaborated into an image where everything

pointed towards the same direction: the enemy is indeed weak and can

be defeated.

Although the New York Times and Dagens Nyheter also wrote about the

weak points of Soviet society and military apparatus, they also gave

more objective appraisals of the effect that the differences in size

and resources between the two countries would have on the outcome of

the war. There were moments when their admiration for the Finnish

soldier made these papers anticipate Soviet defeat, but, once the

Soviet Union had launched a full-scale attack on Finland in February,

they were able to see how the war would end.

The way that the foreign papers

represented the situation remained essentially the same in 1939 and

1940: according to this view, the predatory politics of the great

powers would eventually lead to the destruction of small countries.

One of the victims, the one that received the most attention, was

Finland. In Finland, the war changed the way that the Soviet Union was

represented into a full-blown enemy image, and all available means

were used to boost the people’s will to defend itself.

When one studies the image that the

Finnish press created of the Soviet Union one also has to consider an

accusation that has often been made against Foreign Minister Eljas

Erkko. Are we dealing with, as some people have claimed, with “Erkko’s

war?” If we focus exclusively on the bilateral relationship between

Finland and the Soviet Union, the war is indeed “Erkko’s war.” Finland

could have avoided the Winter War if it had given into Soviet demands

in the autumn of 1939. However, Foreign Minister Erkko chose not to

yield an inch. He forcefully used his paper Helsingin Sanomat to

advance his views and also indirectly influenced the other papers,

which tended to follow the lead of Helsingin Sanomat. Erkko and the

rest of the Finnish Government believed that the Soviet Union was only

trying to pressurise Finland and that it would not start a war in the

middle of the winter. However, things took a different turn and, in

December 1939, Finland was at war with the Soviet Union in December

1939. . When new government was formed Finland got a new government

after the outbreak of the war, Erkko was no longer part of it. On the

other hand, it should be remembered that Finland was never occupied by

the Soviet Union, while the Baltic countries which had given in to the

Soviet Union were occupied already in the summer of 1940.

After the beginning of the war, the

Finnish propaganda organizations carried on their work more

intensively than ever. The media received ready-made pieces to publish

throughout the war. In addition, they were given instructions in which

they were encouraged to write about some issues and to avoid others.

The public image of the war was dominated by current events and by the

old image of Russia and the hated Russians. During the Winter War, the

newspapers created and sustained a clear-cut, strong and emotionally

appealing image of the enemy. The image derived its force from the

historical conflicts between Finland and the Soviet Union and from the

hardships of the current struggle between the two. The negative

features attributed to the enemy clearly served Finnish national

purposes.

However, the Finnish war-time propaganda cannot be regarded as

emphatically right-wing. That the extreme right did not thrive during

the war is indicated by the fact that the Patriotic People’s Front

(Isänmaallinen Kansanliike), the party of the extreme right, had to

close down its other papers in the autumn of 1939 and Ajan Suunta at

the end of the year, owing to financial difficulties. It should also

be noted that the Finnish propaganda during the Winter War was not

modelled on German propaganda or dictated by National Socialist

ideology during the Winter War. Its models are rather to be found in

the Anglo-Saxon world. Finns had been introduced acquainted withto

Anglo-Saxon propaganda work in training courses that had been had been

organized as a form of crisis preparation since the late 1930s.

Official information agencies and the

press worked hand in hand during the war, because the press, too, felt

that it was fighting against thea common enemy. The problematic

features of the image that they had created became apparent only when

the peace was made in March 13, 1940. These problems are partly due to

the fact that the Finnish press had been so effective and unanimous in

representing the way it represented the enemy. The press and the

information organizations had not prepared the people for a peace in

which Finland would loose a large part of its territory, including

loose areas that which the Soviet Union had not demanded before the

war and that which it had not been able to take over during the war.

More than 400 000 people also lost their homes, which meant that about

a tenth of the population had to be was evacuated in a short period of

time. In addition, Finland had to cede the Hanko area to the Soviet

Union, which had already demanded the area before the war in order to

establish a military base there.

The Finnish press was engaged in wishful

thinking concerning the Soviet Union both before and during the war.

In peacetime, it emphasized the weaknesses of the feared neighbouring

country. During the war, wishful thinking was so forceful that the

peace and its terms came as a shock even to well-informed journalists.

The image of the enemy that the press conceived was had been

instrumental in creating unrealistic expectations concerning the war

effort and the ability of the Finns to cope with a Soviet attack.

Takaisin

Studia Historica Septentrionalia 43

|

|